False Positive Affect?

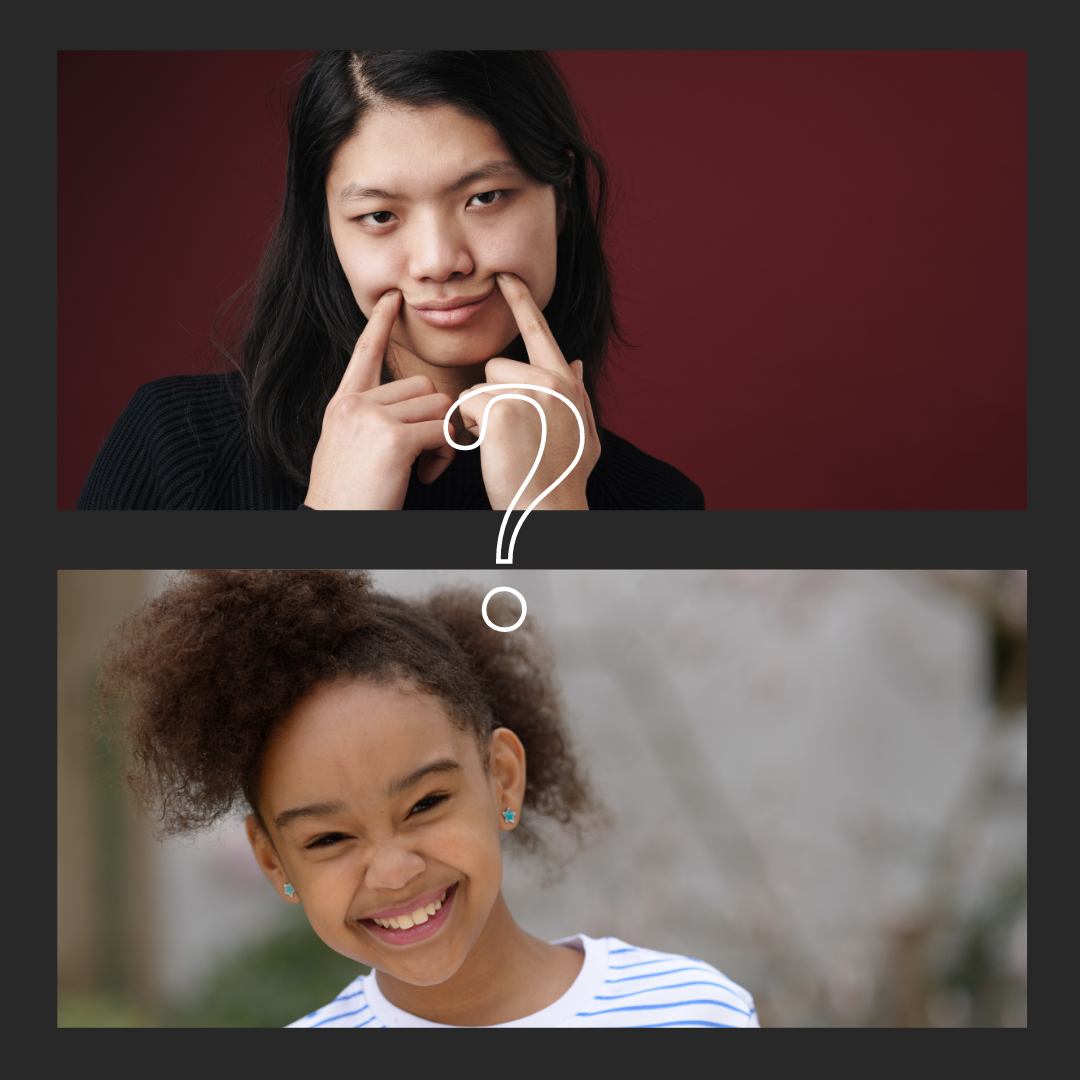

As highlighted by Farnfield and Holmes (2014), one of Patricia Crittenden’s main contributions to the observation of understanding early years development is her work on compulsivity. Crucially for compulsivity, and for children experiencing maltreatment, a strategic response of inhibiting forbidden negative affect can be a child displaying what is known as false positive affect (FPA). For example, from the age of 9 months old, infants who have very withdrawn or unresponsive caregivers may develop compulsive caregiving behaviour. This behaviour may include the child inhibiting their own desire for comfort, and instead excessively focusing on their caregivers and presenting as overly cheerful in an attempt to elicit and maintain attention from their caregivers (Crittenden 2010, cited in Farnfield and Holmes, 2014).

As highlighted by Farnfield and Holmes (2014), one of Patricia Crittenden’s main contributions to the observation of understanding early years development is her work on compulsivity. Crucially for compulsivity, and for children experiencing maltreatment, a strategic response of inhibiting forbidden negative affect can be a child displaying what is known as false positive affect (FPA). For example, from the age of 9 months old, infants who have very withdrawn or unresponsive caregivers may develop compulsive caregiving behaviour. This behaviour may include the child inhibiting their own desire for comfort, and instead excessively focusing on their caregivers and presenting as overly cheerful in an attempt to elicit and maintain attention from their caregivers (Crittenden 2010, cited in Farnfield and Holmes, 2014).

For some children whose caregivers punish displays of affect, it can be too risky to develop coercive strategies to elicit responses from their caregivers. As these children still require ways to elicit responses to enable their needs to be met, they learn that the use of coy behaviour such as smiling and being cute is welcomed by their caregivers (Crittenden, 1992 and Winnicott, 1958, cited in Atkinson and Zucker, 1997).

The display of FPA is intended to enable a child to avoid punishment or rejection, and it is used to help the child elicit caregiving and/or approval (Crittenden, 2016). Furthermore, for children who have frightening and angry caregivers, learning how to act happily can be self-protective (Crittenden, 1992 and Winnicott, 1958, cited in Atkinson and Zucker, 1997), and the use of FPA can function to deceive and improve the child’s relationship with their caregivers (Crittenden, 2016).

Professional observations of Victoria Climbe provide powerful examples of how FPA can be misinterpreted for genuine displays of positive affect. Victoria was only 8 years of age at the time of her tragic death, with her death being the result of her being subjected to significant physical abuse by her great aunt, and her aunt’s partner. Although numerous injuries to Victoria were noted by medical professionals, and there was extensive involvement by Children’s Services and the police, it was concluded within the Lord Laming report (2003) that numerous opportunities were missed to prevent Victoria’s death.

Without implying that a greater understanding of FPA would have prevented the death of Victoria, Crittenden has highlighted interesting observations of Victoria’s presentation while she attended hospital for treatment to her injuries. For example, it was noted by professionals that Victoria presented with a happy demeanour and she was described on one occasion as a “ray of sunshine”. What could have been deemed as inappropriate displays of affect for a hospital environment, Crittenden has pointed out that it appeared difficult for professionals to recognise Victoria’s displays of FPA (Neven, 2010). Victoria’s use of FPA may have been an attempt to hide her negative affect (including feelings of fear and anger), as if she displayed her genuine feelings, it could have increased the abuse that she was experiencing – for example, Victoria’s aunt and/or partner punishing her for drawing attention to what was happening within the family home.

With an extensive history of working within frontline child protection, I know all too well how easy it is to make assumptions about a child’s emotional presentation. I have to confess that I have historically spoken to and observed many children who were subject of child protection intervention, and on recording my observations, I did not question whether the child’s displays of affect were appropriate to the context of what was happening in the child’s life. Since learning about the work of Crittenden and the Dynamic Maturational Model (DMM), including Crittenden’s thoughts about the strategic use of FPA, I now ensure that I always question my understanding of a child’s emotional presentation. Of most importance, and as highlighted by Crittenden, when assessing children who are at risk of harm harm and/or abuse, I now ensure that I view children’s emotional presentation as a form of communication within a developmental and relational context (Neven, 2010).

Engaging with caregivers:

Consideration should also be given to FPA when engaging with caregivers. For example, when speaking to caregivers, you may encounter FPA when the affect expressed in conversation is inappropriate to the emotional content of what is being discussed. This may include a caregiver laughing or joking while commenting on events which you interpret as traumatic or emotionally distressing. If you encounter this, it is possible that the caregiver may be using FPA to dismiss or avoid the difficult feelings that are inherent in what is being discussed. Apart from the need to be curious about the potential meaning behind the caregiver’s emotional presentation, if you feel it’s appropriate, try to empathically reflect back the incongruence of what you observed and explore the caregiver’s views about the potential meaning of their behaviour.

References

Atkinson, L. & Zucker, K. J. (1997) Attachment and Psychopathology. New York, The Guilford Press

Crittenden, P. M. (2016). Raising Parents: Attachment, representation, and treatment. Oxon, Routledge

Farnfield, S. & Holmes, P. (2014) The Routledge Handbook of Attachment: Assessment. Hove, Routledge

Neven, R. S. (2010) Core Principles of Assessment and Therapeutic Communication with Children, Parents and Families: Towards the promotion of child and family wellbeing. Hove, Routledge

For more information about the tragic death of Victoria Climbe and the findings from the Lord Laming inquiry, please visit:

www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-victoria-climbie-inquiry-report-of-an-inquiry-by-lord-laming

If you are curious about FPA and its strategic use within the DMM, I would strongly recommend Patricia Crittenden’s book, Raising Parents: Attachment, representation, and treatment (2016)

Attachment Theory and Children’s Social Work Practice

According to Shemmings (2015), attachment theory is one of the most well-known theories used in child and family social work and is a popular lens through which social workers can assess parent-child dynamics.

Reference to attachment theory and social work dates back to the social worker, James Robertson who, through his work at the Tavistock Clinic with John Bowlby, put forward early empirical evidence for Bowlby’s ideas about attachment theory. Robertson’s evidence was gained from undertaking close observations of young children, who were highly distressed when having to go into hospital or foster care, meaning they were separated from their parents (Howe, cited in Holmes and Farnfield, 2014). Following on from the work of Bowlby and his colleagues, such as Robertson, researchers like Main and Solomon (1986) and Crittenden and Ainsworth (1989), transformed social workers’ thinking about the causes and consequences of child abuse and neglect (Howe, cited in Holmes and Farnfield, 2014).

Attachment theory has continued to play a fundamental role within social work as it has helped create invaluable links between children’s emotional development and behaviour and the quality of their relationships with their parent(s) and other attachment figures (Trevithick, 2005). Furthermore, research in attachment theory has helped social workers create ideas for how the effects of adversity in early life experiences, including separation and loss, can impact children’s developing minds, emotions and behaviour (Cocker and Allain, 2008).

Although Bowlby’s original ideas of attachment were perceived as hard-wired and fixed within the early years of life (Stacks, 2010), social workers now have access to new and ever-evolving research. For example, Bowlby initially identified the mother-child relationship or bond as being of most importance, but later revised his thoughts and gave prominence to the forming of attachments to other significant adults in a child’s life (Bowlby 1988, cited in Trevithick, 2005). For social workers working within diverse and transient cultures, for instance, in the United Kingdom, such changes to the early ideas of attachment are important to consider as the roles and dynamics within families are forever evolving.

As the Dynamic Maturational Model (DMM) is the only attachment theory based on observations of maltreating samples, and follows three decades of research on child protection populations (Crittenden 1981, 1998, 1999 and 2008, cited in Crittenden et al, 2013), it could be considered an important model for social workers because it defines attachment in a way that is relevant to families who harm their children (Crittenden et al, 2013). By drawing on the ideas and findings from many approaches to maladaptation, the DMM, unlike other theories, also addresses adaption and considers that in some context, all protective strategies should be seen to be a strength (Crittenden et al, 2021). Of potential significance to social work practice, fear in the ABC+D model has a dis-organisational effect on attachment category, whereas in the DMM, fear has a highly organising effect on attachment strategies (Holmes & Farnfield, 2014). This difference could be considered vital for child protection practice, with social workers needing to understand the impact of harm when children are exposed to behaviours and environments that evoke fear (including fear for their emotional, psychological and physical safety).

Food for thought:

As suggested by Shemmings (2015), is attachment theory one of the most well-known theories within children’s social work? If so, how confident are social workers with their understanding of the theory, and are they confident with using the theoretical ideas within their daily practice?

Are children’s social workers aware of the DMM, and if so, are they confident with applying the concepts within their daily practice?

If children’s social workers are not aware of the DMM, why not? Should all social workers not be trained in the basic concepts of the DMM considering it is the only attachment theory based on observations of maltreating samples?

I would love to know your thoughts….

References:

Cocker, C. & Allain, L. (2008) Social Work with Looked After Children. Exeter, Learning Matters Ltd

Crittenden, P. M., Farnfield, S., Landini, A, & Grey, B. (2013) Assessing attachment for family court decision making. Journal of Forensic Practice, 15 (4), 237-248

Crittenden, P. M., Landini, A., & Spieker, S. J. (2021) Staying alive: A 21st century agenda for mental health, child protection and forensic services. Human Systems: Therapy, Culture and Attachments, 1 (1), 29-51

Holmes, P. & Farnfield, S. (2014) The Routledge Handbook of Attachment: Implications and Interventions. East Sussex, Routledge

Shemmings, D. (2015) How social workers can use attachment theory in direct work. Available at: www.communitycare.co.uk/2015/09/02/using-attachment-theory-research-help-families-just-assess/

Stacks, A. M. (2010) Self-protective strategies are adaptive and increasingly complex: A beginner’s look at the DMM and the ABCD models of attachment. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 15 (2), 209-214

Trevithick, P. (2005) Social Work Skills: a practice handbook. New York, Open University Press